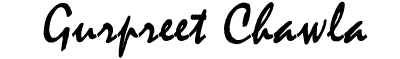

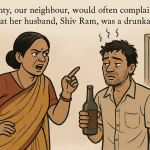

Aunty, our neighbour, would often complain that her husband, Shiv Ram, was a drunkard.

My father drank too, but my mother never complained.

Shiv Ram uncle was a lean man with a thin moustache and black plastic spectacles that forever slipped down his nose. His half-sleeved shirt was never tucked in, and his feet, even in winter, knew only sandals.

He worked in the same office as my father but left home much earlier, walking the few kilometres to work while my father rode his scooter.

Each morning, he set off with a black umbrella in one hand and two rotis with mango pickle wrapped in an old newspaper in the other. A folded Indian Express rested under his arm. He walked calmly, as if time itself had slowed to his pace.

In the office, he was a clerk—keeper of files, typist of letters and memos, a man whose quiet diligence went unnoticed. His colleagues mockingly called him Professor, for he spoke in polished English and read editorials with the seriousness of a scholar.

He was, in fact, a first-division graduate in English Honours. He could have done better in life, but fate had other plans.

The sudden death of his father and the burden of younger siblings had forced him to take the first job that came his way.

At lunchtime, when others went home for their hot meals, he would sit under the peepal tree in the office lawn and eat his cold rotis with pickle.

Then, with unhurried grace, he would open his newspaper and read until the bell rang again.

He never said no to work. Often, he helped others finish their files and typed their drafts. He was always the last to leave.

In the evenings, he walked to the roadside workshop of his friend Javed, a scooter mechanic.

While Javed fixed carburettors and brake cables, Chotu, the helper, would hurry to the theka for a quarter of whisky.

In the fading light, Shiv Ram uncle sat on a broken chair, sipping his drink from a steel tumbler, discussing the news of the world with a quiet intensity.